While I was in my neglected hobby area yesterday to collect some things to entertain my eldest (who is still quite young) I saw something that gave me pause.

While I was in my neglected hobby area yesterday to collect some things to entertain my eldest (who is still quite young) I saw something that gave me pause.

Having spent a considerable amount of time at sea, navigating everything from small sailing vessels to major surface combatants, from the Inside Passage in the Pacific Northwest to the Middle East, from Alaska across the Line to Valipo Bay, I have a keen interest in all things maritime. Pilotage techniques and celestial navigation are particularly close to my heart – yes, I have a sextant and two astrolabes at home (and more fun toys at work). When navigation and my gaming hobbies collide it’s wonderful! Or is it?

Well, quite frankly, more often than not I am frustrated and disappointed (unless the game or work is centred around the sea). I find the baseline knowledge of seamanship in the pre-industrial age deplorable.

I am hoping to use this post to rant a bit and also hopefully educate. Don’t Split the Party has an excellent post on the perception of distances in the medieval world. I aim to have this post do the same for waterborne travel; to inform those creating their own worlds, whether for gaming or fiction. This is a very broad topic I’m just touching on the surface of it, so if you have any questions or comments, please feel free to comment below or send me an email.

Utility and Speed

Movement on the water in many wargames, novels, and RPGs is so slow and uncertain. Achingly slow. Ships are lucky to make 30km a day. In several campaign games and computer wargames (Total War series, I’m looking at you! Pliny talks of sailing from Rome to Spain in 2 days, not a year!!!), movement on the water is so sluggish that it seems to be intentionally bad, rather than an oversight, perhaps to put the focus on land warfare rather than on seapower. Novels, RPGs, and campaign settings are often no better, with a mix of well-designed ships of the line moving slowly and cautiously always in sight of land.

This sadly feeds into the idea that early mariners were terrified and incompetent and that the sea was a barrier rather than a highway. Yes, storms at sea happen and yes, ships were (and are) lost during voyages but reality about the utility of sea lanes and vessels is much different than portrayed.

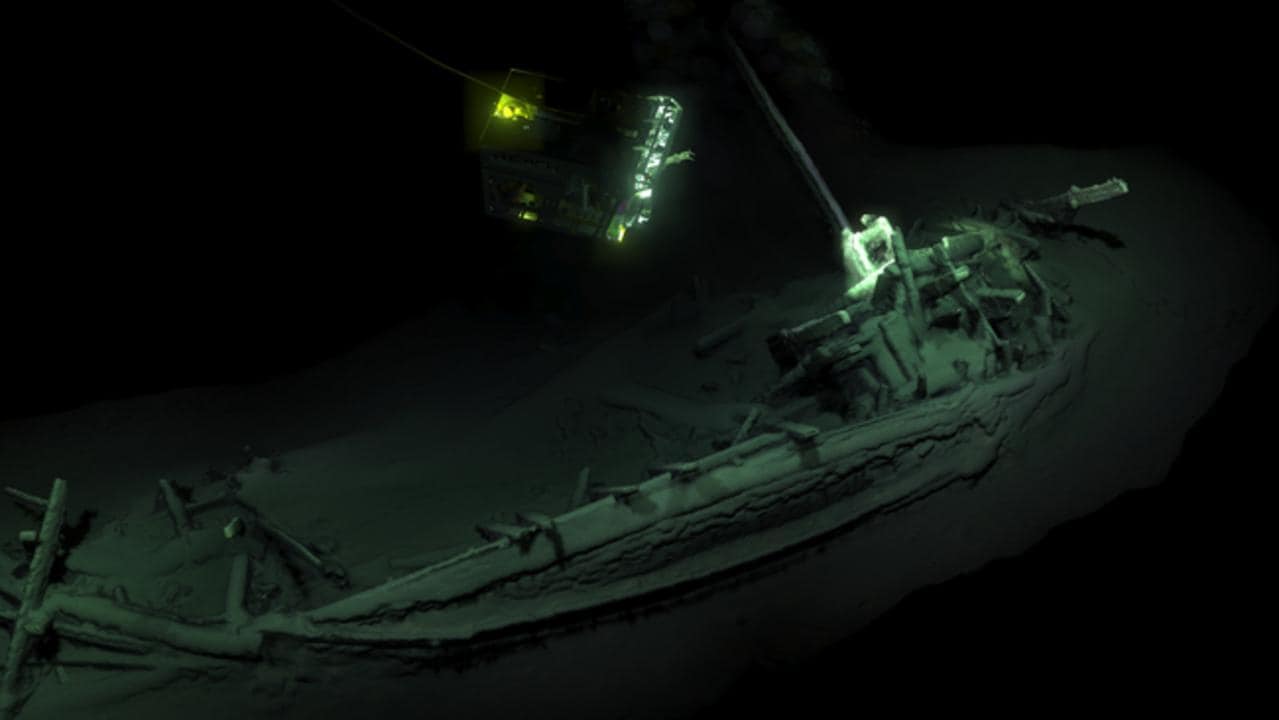

Take a look at this (the feature picture is from the article). A simply amazing discovery! That old cargo vessel would have been quite fast. How fast? Recreations of similar ancient cargo vessels have them making 3 knots consistently, even against the wind; 4 to 5 kts if they were running with. This is backed up by ancient sources that detail record and average sailing times between major ports. What’s so fast about a measly 3 knots you say? That’s just a walking pace!

Well, unlike animals, ships don’t have to take breaks or sleep, and they carry a lot. The first recorded vessel that was in a shipwreck was 180 feet long (3,500 years ago). Ships have long been very useful at carrying cargo and personnel. And if you have confidence in your position or can see via natural illumination, you can carry all that stuff and keep going even at night.

Let’s look at this more closely. Worst case scenario, assuming you are new to the sea and not comfortable to sail at night, and are following the shore rather than cutting directly to your destination, how fast can you go?

During the day you creep along in sight of the coastline and then stand out to deeper water at sea at night for safety (the closest danger to a ship is almost always under her keel). As the Sun sets into the sea, you are looking at about 36nm travelled that day from twighlight to twighlight. That’s 41 miles or 66 km. Every. Single. Day. People attempting the same journey on foot would be left well behind, especially if they are forced to walk around the body of water (potentially through hazardous territory). The Mediterranean was the highway for international trade, not a barrier, as many games would have it.

Right so 36nm a day is low as an estimate for average ships at sea. On good days, even with only rudimentary navigation skills, having illumination from the Moon and stars, you could easily continue along the coastline at night. That then becomes 72nm (82 miles, 133km) per day with a poor master in charge of navigating who is hugging the coast rather than heading straight to the next port (which would shave off a huge amount of distance). There is no pre-modern army that can move anywhere near that fast, especially not carrying supplies. Even individuals changing horses at imperial postal inns wouldn’t be able to keep up, especially once you leave the coast and sail directly to your destination.

Adding to sailing non-stop and cutting across the open water where you can remain on a tack for a long period of time, you can even double that already impressive speed. If you have a reasonable understanding of navigation 24 hour voyaging in the open sea is easy. This means that you could be making 150nm+ (172 miles, 278km) days along certain routes (and even faster in the Age of Sail).

Trade Routes

Now winds don’t always go where we want them to, beating upwind is slow, hard work, and stemming a current or tidal stream can be a maddingly sluggish crawl. So how does that fit in with the data of rapid sea voyages? Well, voyage planning was key. Much like modern mass transit systems, many trade routes weren’t direct. They took advantage of prevailing winds, tidal streams, as well as ocean currents. This means that vessels would sometimes find it faster to go from A to B to C, and then back to A, rather than just reversing course and fighting upwind or up current from B back home. If your characters, armies, or special delivery needs to go to a specific place, keep this in mind when world/plot building This is exacerbated by regional weather patterns and the impact of the seasons.

Seasons and Weather

It was long held in the Greco-Roman world that voyaging from October to April was dangerous. From my experience in the Mediterranean, the winds do indeed become more capricious and early October can see some significant storms that would have challenged earlier vessels. A particularly memorable (Canadian) Thanksgiving south of Sicily had us hove-to in some quite impressively bad seas, even for a modern warship. I ate so much that night as there were few who could stomach turkey and stuffing! As I gorged myself, I thought of how ancient writers had forecasted the sudden and drastic change to the character of the sea.

Seasonal voyaging and voyage planning gives real flavour to a world or story. So instead of having slow ships in a fantasy world or historical campaign, have them be fast and reliable, until a certain month. It adds tension when you must decide if you are to go sailing in the Winter. Ships will be delayed or never arrive. Long journeys by foot, though undesirable, may become necessary after the stormy season arrives, at least until Spring unless you’re willing to chance disaster. All of this means added complications or obstacles to be overcome, and obstacles and challenges are really points of friction and interest in both wargames, RPGs, and writing.

Lost at Sea

What about voyaging beyond the edge of land? Well, if you do it during good weather, it’s not that hard, even without GPS. Latitude is a simple problem to solve, and latitude hooks of various forms have been used at sea (and in the desert) for many hundreds of years (latitude hooks are simple tools to measure the altitude of the North Star or the Sun. If you know the latitude of your destination, you simply head north or south until you reach that latitude and then sail due east/west). Remember that it was not until the second half of the eighteenth century that the longitude problem was solved (for those interested in that, have a read or watch of Dana Sobel’s Longitude) so most of the world was sailed across using relatively simple tools.

While a compass is hugely useful there are ways of finding direction at sea as long as you have clear skies. Even when the skies are cloudy, there are options: the Vikings (and maybe others) found a way to see through the fog and grey skies of the North Atlantic. Having an idea of where north is, it’s not that hard to keep a course.

Old charts (like the one above) were less geographical representations, than sailing directions that delineated the course to steer from one port to another. Ships didn’t plot their position on charts as much as look for distance run along certain courses. Work could be checked by comparing the estimated latitude and your distance run. When things went bad, the ship would head for the correct latitude and then sail east/west. By being mindful of sealife, birds, and land/sea breezes, kelp beds, etc, a mariner can get early warning of coastlines and arrange to get closer during the day to establish their position, (to learn how Polynesians navigated using natural signs, I highly recommend We, the Navigators, which is illuminating and humbling all at once).

Rivers as Roads

Watercraft are also extremely useful on inland waterways. Water is not just useful to travel on at sea. Rivers are the roadways of the pre-modern world, though they often form barriers in fantasy worlds, with forces lining the bank staring hard at each other. Rivers were important as lines of communication, not boundaries for foes. Look at the Romans – they pushed past the Rhine to secure it and used it as a means of transportation for centuries. Even in Winter, you can have 10 hours of light, and using the current, sails, donkeys pulling lines, oars, etc, you can make a good distance each day. Heavy supplies, enginering works, building materials, and combat forces were transported quickly and effectively by rivers in ways that were only surpassed in the last 150 years by rail.

Technologies of the Sea

In many tales you have ships from the age of sail alongside late (or even early!) medieval tech. This is so very wrong. The engineering and scientific knowledge, let alone the supply-chain management that goes into a ship of the line makes this laughable and really breaks the suspension of disbelief.

The complexity of tall ships is staggering. Miles of standard sized cordage, hundreds of blocks, and thousands of planks are needed, requiring a uniform system of weights and measures and massive specialized labour forces (and the developpment of milling technology). The hull design itself is predicated upon heavy guns, which again need to be cast with the same bore size and limited variance from gun to gun requiring advanced metallurgy. If you have 2 or 3 deckers, you need to have fleet organizations and tactical signalling, as the creation of those ships was based on the commanders of large fleets having difficulty of concentrating firepower due to short effective gunnery ranges and limited arcs of fire. Without the need for concentrated gunfire, it would be easier to concentrate power by using more numerous, lighter ships.

The social and market technologies that enabled the age of sail are particularly overlooked. For example, think of stock exchanges. The basis of the modern bond market came from the astronomically high cost of building a navy during the age of sail. Governments needed capital, and Britain was the first to figure out a simple way of raising capital quickly – government bonds. Other countries followed suit. So if you have ships from the 17th century or later, you should have a stock exchange to boot.

I could go on, but you see the problem. Simply dropping in tall ships without thinking about how (and why) they were made is a real problem. Earlier sailing ships were more simple and may be harder to conjure in the mind’s eye, but they were still capable vessels in their own rights and made tremendous voyages. Using them goes a long way in creating a consistent world.

What about Magic and the Fantastical?

Magic can change a lot of things, but too often is over-used and under-thought of to give a believable, internally consistent world. I will do a more detailed post in the near future on some thoughts on magic, but here are some quick points.

Necessity guides invention, so if magic provides a solution, technology will not attempt to. Magic is, in essence, a type of technology. So if there is a spell that does “x”, a society will not develop a mechanical or social solution to do “x”, that problem has already been solved. If fast travel is possible by magical means (spells, creatures, gateways), it is likely that advanced shipbuilding won’t have been pursued. No one needs a fast ship to carry a message when a hippogriff can cover the same distance in a day. If gates are available, moving goods or masses of troops would be much more efficient than by water.

If these magical solutions exist, but you still want real-world solutions to be used, you need to come with a reason as to why the fantastical is too costly, in blood or treasure. Perhaps travelling through magic gates becomes more risky the more people who go. Perhaps magic travel ages you. All of this creates friction and could still end up with some real-world maritime tech.

Rant Complete: we are free to manoeuvre

The sea has always afforded flexibility. You can strike where you please, when you please (like the Vikings). If you are worldbuilding or game designing, consider the operational freedom that waterways provide, for trade and for war. Have rivers be objectives not as defensive lines, but for the movement of supplies. Think of the technologies needed for travel and navigation, and the character of the weather and seas in your lands. If you are working on a wargame, don’t undersell the impact of sea lines of communication upon the battlefield. Taking the time to understand the environment, the technology in use, and the points of friction that exist in those environments gives verisimilitude in games and in novels and keeps pedantic sailors like myself happy.

P.S. For those looking to dive in to the world of movement on the water, Lionel Casson’s works on ancient shipping are an excellent introductions on the technology of watercraft in ancient world.